- Artwork by Eli Jorgensen

Becca Kennedy teaches us how to do UX research on a budget. She encourages newer designers to demonstrate their problem-solving superpowers by redesigning sub-par experiences they use regularly. She reminds us that users are human before they’re users. She also shows us how we can have anything in life we want, if we will just help others get what they want.

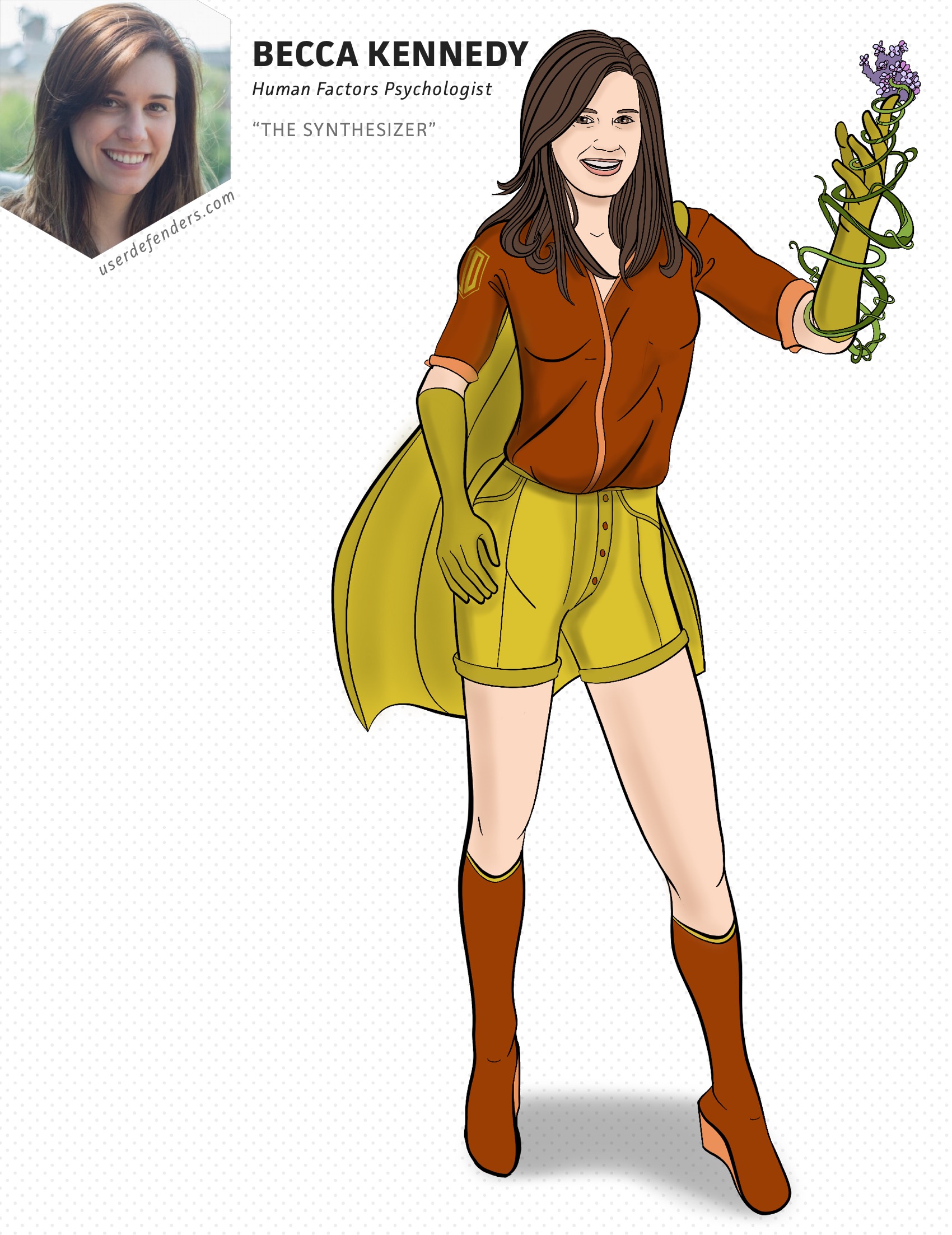

Becca Kennedy is a Human Factors Psychologist and a UX Researcher/Designer. After an academic career designing and evaluating healthcare training technology, she turned independent and co-founded a UX consulting company called Kennason in 2015 out of Albany, NY. Currently, Becca is the UX Designer for Agrilyst, an agriculture-tech startup based in Brooklyn. She also keeps busy with consulting projects and volunteering with organizations like AIGA Upstate New York. She was recently recognized by the Albany Business Review as a 40 Under 40 awardee. Fun Fact: She has three tattoos, and all are kind of nerdy: a symbolic nod to getting through a PhD program, a subtle Star Wars X-Wing, and a piece of the original Epcot branding in Walt Disney World.

- Becca’s Tattoo’s Origin Story (5:31)

- Why Psychology? (6:26)

- What is Human Factors? (11:43)

- How do we find research subjects? (24:06)

- The Law of Diminishing Returns (31:16)

- Awkward Testing Story (32:57)

- Design Superpower (39:14)

- Design Kryptonite (40:48)

- Coping with Imposter Syndrome (44:49)

- UX Superhero Name (49:10)

- Should we Call Them Users? (53:45)

- Fights for Users (56:33)

- Habit of Success (59:11)

- Invincible Resource (61:54)

- Recommended Book (63:54)

- Best Advice (66:09)

- Contact Info (70:07)

LINKS

Becca Kennedy’s Twitter

Becca Kennedy’s Website

How good UX can save lives [ARTICLE]

Alphonse Chaponis

Designing for Human Brains (UX Burlington) [VIDEO]

User Researchers…Enjoy the Silence. [ARTICLE]

Do you Trust Your Robots (Becca’s preso mentioned)

Issac Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics

Imposter Syndrome: Why We Have it, and How to Kick it in the Privates [PODCAST]

Banish Your Inner Critic with Denise Jacobs [PODCAST]

In defence of the term ‘users’ [ARTICLE]

Becca Kennedy’s Articles

Albany Can Code

A 100-Year View of User Experience [ARTICLE]

RESOURCE

Mixed Methods Slack Channel

Interaction Design Foundation Courses

BOOK

The Design of Everyday Things

TRANSCRIPT

Show transcript

Jason Ogle: Welcome to User Defenders, Becca. I am super excited to have you on the show today.

Becca Kennedy: Thanks Jason. And I thought, forgot I gave that fact to you about my tattoos. That’s awesome.

Jason Ogle: I love it. I’m so glad you did that. It’s a fun icebreaker, you know, that’s why I asked for that. It’s a neat way. And I am curious. Tell me about if you would, I’d love to know what the symbolic nod to the PhD program is and where might that be?

Becca Kennedy: Oh yeah, totally. And that’s my most visible tattoo on my forearm. It’s a lilac. And the reason that symbolic is, I got it when I finished my PhD, and it kind of symbolizes that first sign of spring if you live – I live in upstate New York. And if you live up here, you know that when you see lilacs bloom, like spring is finally here. But the idea there is that lilacs bloom stronger after a cold winter, like you really need that freeze to bud and bloom, so, I like the symbolism of that and that I had to get through some maybe cold, chilly dark times to bloom.

Jason Ogle: I really liked that a lot. You are a deep person Becca I can already tell that. I mean that’s on there for life now and there’s a lot of symbolism to that. And why psychology, like what was it about psychology that drew you in? Was it like, did you read a book early on that kind of drew you in or did you have family members that had a background or what was it exactly?

Becca Kennedy: Not at all. It was just kind of a hunch. So after taking my intro psychology course in high school, I was just like, yeah, this is cool, this is really cool to just start learning about like how the brain works and of course at the psych 100 level every example you get, it’s just so cool and mind-blowing because you’ve never thought about like how memory works or how we become the people we are, and at a young age kind of being introduced to that I kind of ran with it. I did, one summer, I worked for the Psychiatric Center in Albany and that was also not for me, so you can see there were a lot of things in life I tried and was like, nope, not quite. It would have been way too draining for me to do that kind of thing for a career.

And then my senior year of college I did some research about what I could do as a psychologist that was not clinical and found industrial organizational psychology or IO psychology and took a course on that mainly because I read in a careers book that you only needed a master’s degree to practice as an IO psychologist. And I did not want to commit to a PhD at that time. And when I was taking that IO psychology course with Dr. Dorian Comerford, who I’m still actually in contact with, she’s a wonderful woman. I think one class on what’s called human factors psychology, one single class. So, one day, where she talks about like the world around us and how it’s designed and how she showed an example of a vacuum cleaner she has where the on switch was like not visible when you’re looking down at the vacuum.

And this was about a 2008, user experience wasn’t like it existed in some forums, but I had certainly never heard of it. So, human factors was the closest thing I’d heard to what would become my user experience career, and on a whim almost decided I was going to go get a PhD in human factors.

So, I applied to some programs, ended up getting into a few and I went to Old Dominion University for my PhD, which I decided on because first of all, there are not that many human factors programs, especially not those in psychology. There are some that are engineering, and like I told you, engineering was not for me. So when I went and visited they were just showing all this really cool stuff they were doing with virtual environments or virtual reality simulations, video games. And I just, that just like blew my mind that you could do research on the human brain using that kind of technology and then use it in an applied setting.

So, when I joined that program, I ended up working in healthcare a time. And in about 2011, 2012, I found UX, somehow I’d probably on twitter or something, and I realized people were doing all this stuff that was similar to human factors, but in more of a consumer space as opposed to like a safety healthcare, like critical context. And I thought, yeah, this finally, that’s where I was trying to get with all this was like designing stuff using psychology and using research and all that. So, is that enough of an origin story?

Jason Ogle: Yeah, though it’s actually. I appreciate the deep dive there because; you’ve obviously really worked hard to get where you are today, and I love that. And that’s really the reason the show exists is to inspire, especially those up and coming, you know, design superheroes as I fondly refer because you know, and you’ve written articles a lot of articles on the user [inaudible 05:27] and things. And I really enjoyed your article about how good UX can save lives. I feel like that’s sort of like the pinnacle of opportunities that exist in this field in my opinion, when you can save a life through good design, that’s a pretty big deal. And so, I think that was the first thing that can actually kinda drew me to you. I saw your article there as like we got to talk, you know, because I mean, I love psychology too and it’s really been more of a recent foray for me to be honest with you.

And it all started with just by reading some books and just getting really excited about the human brain and behaviors, human behaviors that are so many parallels to human behaviors and design and effectiveness of design, and of course or not. Well, let’s talk about human factors because I feel like that’s kind of one of those less used phrases in our field. But yet it’s really like UX, the whole discipline and practice, it goes, it stems from human factors, discipline and study. Can you talk about that? What is human factors?

Becca Kennedy: Yeah, definitely. I had a feeling that question was coming. So yeah, and in fact there have been a few talks recently that I give to UX crowds on where I include a slide that’s kind of like the history of UX or at least when like branch of it and I talk about human factors. I really starting from like the industrial revolution where researchers first started thinking about humans as part of a system and wanting to make them more efficient.

Jason Ogle: Can I stop you there real quick? Can you go because; I actually saw your talk recently, the one that’s on, I found one online actually, and this might be the one you’re referring to where you do talk about the history of human factors and you mentioned the industrial revolution, and every time I think of the beginning of user experience design and/or human factors as it was known then I think of a Alphonse Chapanis and his work in aviation, which was incredible by the way. So that’s kind of, for me, that’s where the timeline always began for me. And then when you mentioned the industrial revolution that really perked me up. I was like, Oh, I want to ask her. I want to learn more about that. Like tell us more about like how human factors started even then because I mean we’re talking a 100 years ago plus.

Becca Kennedy: Yeah, definitely. I think the talk you are referring to is from an event called the UX Burlington, which was in Burlington, Vermont.

Jason Ogle: That’s the one.

Becca Kennedy: called crowd proof. And that was a really great event for anyone using the Northeast or wants to travel there that I was very, very impressed by that event. But yeah, so I think in Grad school when we learned about human factors and my program was actually human factors and ergonomics. So, ergonomics is two things; either it’s kind of like the British were European term for human factors or it’s like the physical part of it. So, one way I can explain human factors is that, you know, most people are a little more familiar with the term or a lot more familiar with the term ergonomics because we’re familiar with, you know, Ergonomic chairs and desks and laptop [crosstalk] law suits, keyboard. Well, exactly. So ergonomics means you’re designing something to fit the natural human body is what that means. So you don’t want to strain it, you want things to fit the way the body’s built and human factors is really the same thing, but for the way your brain works.

So, you are designing things to fit how people think. So, the way their brain fits into whatever you’re designing. Sometimes that clicks for people because you can relate it to stuff you’ve physically seen in use that’s Ergonomic and think, okay, same thing, body brain connection, I get it. But yeah, the industrial revolution is when what are called time and motion studies started. So for example, researchers watched people shoveling coal, watched men shoveling coal and determined that there was an optimal weight for how much coal should be in the shovel so that they are as fast and efficient as possible. So, it’s a lot of mathematics. It’s not really thinking of people as like human beings with feelings or anything, but it’s just thinking like, well, as part, you know, we want to shovel as much as possible, here’s the person doing it, might as well be a wheel in a cog, but they’re a person.

So, then they designed a shovel that would hold that optimal amount of weight so that they’re getting the output they wanted. So, this is kind of a trend for at least the first bunch of decades of ergonomics and human factors. And the roots of that is just like, how do you design something so that the person works better in the system? And you mentioned aviation while if that’s where it kind of exploded in World War II times, you know, was how do we design, say, an airplane cockpit so that pilots are able to use it without crashing. So up until that point, it was kind of, engineers would build things and then it would be up to training, it would be up to the people to learn how to use whatever it was.

So, there wasn’t really a whole lot of forethought about– well, what, how do we design this past, it was just we’re going to build this and you’re going to learn how to use that, even if the dollars make no sense, even if the information you need to look at the same time as two opposite sections of the same, you’re going to learn. So again, it was kind of for efficiency and safety that people even started considering the person as part of the system and designing for them.

And of course as technology evolved and as we got software on the World Wide Web and mobile phones, it’s all involved with it. And now, we have UX which in my mind is more about the subjectivity involved. So, it’s thinking of people as actual people. So you want them to not just be efficient, but you want them to enjoy what they’re doing or at least not hate it.

Jason Ogle: Yeah. I think Henry Ford too. I’m sure there was a ton, and again, it’s probably not reported as much, but one can only guess at the efficiencies that they were striving for. I mean he even had efficiency experts that would go around it. This is the true story because I’ve read about this. They would go around the factories and they would just have their clipboards in hands and they’d be like the “Two Bobs”. You remember in “Office Space”, the Two Bobs that were actually, always looking at people to see if they weren’t contributing enough, you know, and nobody wanted the two bobs and their meeting. But that’s he had hired people that actually were called quote unquote efficiency experts and so no doubt that was just make sure that they were adhering to the user experience that they establish for building vehicles and on the assembly lines and such.

One of my favorite stories related to that was whenever the efficiency expert would always walk by and there’s one office, he would always walk by and he would see this fella with his feet up on the desk looking out the window and he like, this happened like multiple, multiple times, and he finally reported it to Henry Ford and he said, yeah, there’s a problem, this guy, whatever so, and so, you know, he sits on his desk all day, with his feet up on the desk and is looking out the window. He’s not doing anything like what’s up with this and you know, I think he should be fired that guy, you know. And then Henry Ford said, oh, that guy, yeah, you know, what he once had an idea that saved me millions of dollars and he thought of it in the same position!

Becca Kennedy: Oh my God.

Jason Ogle: Isn’t that great? That is a true story. And I love that. It’s a good reminder for all of us, you know, because; they’re just slow down a little bit. I mean, I think some of our best ideas can come and only come when we actually put our phones down, put our screens away and like go for a walk and right, and like, get away and unplug and I think that’s so relevant.

Becca Kennedy: Yeah, absolutely.

Jason Ogle: So anyway, I’m getting off on a tangent there, but I just loved that. So, human factors, that’s really, I love how you said that’s like, it’s sort of like what we look at as physical ergonomics. It’s like that for the brain, like I love that is so important in our field today, I feel like there’s so many experiences that are unleashed upon society that it almost appears as if nobody, if they created the thing ever used it, or even considered human factors are considered, you know, other humans in this thing. Do you have, does that bother you? Do you have any thoughts on that on how that happens and why that happens so often?

Becca Kennedy: Yeah, I mean of course that bothers me. Of course, it seems like something that’s common sense to us because it is, but it’s really not to everybody. A lot of times people just want to get products out the door, like they want to be the first to market in a specific area and they just don’t have time or resources they believe to take care of something like the user experience when in fact that should be the backbone of what they’re actually building. Right? Yeah!

So, I mean there, it stems from a lot of things to, I mean the term UX being thrown around and people not really knowing what it means, but knowing that it’s kind of a Silicon Valley buzzword contributes to that and when you’ve got people quote unquote practicing UX who don’t really have much of a research background or psychology background or an appreciation for that can kind of a cheap and what the field seems to be, right? Because; if you’ve got people not representing us too well, I guess is the nice way of saying it kind of dilutes things.

Jason Ogle: Interesting! I just launched an episode with Alan Cooper and I put a tweet out there, I tried to like, you’ll grab some kind of quotable tweet out there to promote the episode and the one that he retweeted was today that obviously got a lot of traction after he retweeted. It was a quote from him, but I loved it. He said something about to the effect. We’re talking about bad products, why do they exist? And he said, “the reason so many bad products exist is that the people making bad products don’t want to make good products. They want to get promoted to VP.”

Becca Kennedy: Yeah! Oh man. Yeah. I listened to that episode the other day and that hit me too. I was like, man, yeah. Like you want to rise up, right? You want to, you’re not doing production work anymore. You’re not doing the research part anymore. Like it’s passed down further and further.

Jason Ogle: Yeah. And it’s sad because I understand wanting to succeed and obviously we need to make money, you know, and the cost of living and everything, it keeps going up and it’s a problem if our salaries do not. So I get that. But I’m frustrated when greed is at the focal point of building products, when greed or status or things like that, because then what, who gets forgotten the users, the people that the product was intended for it intended to help, right. And of course there’s probably designers that are lower on the totem pole that know that they’re shipping crap that’s going to, you know, be unethical and things like that. And probably having a lot of crisis, you know, moral crisis sees. You know, I think it’s just a real shame and I feel like I want to see a movement and I hope that even Allen’s episode will kind of start more conversations around that problem, and especially that stems out of Silicon Valley.

Becca Kennedy: Yep, exactly. I mean, there’s people, so, it’s the Ian Malcolm Jurassic Park thing, where are you spending so much time thinking about whether you can do something, are you stopping and thinking about whether you should or in UX sense how, what’s the best way like, and what are the implications of what you’re building, you know?

Jason Ogle: Exactly! Right? I want to take a step back, you mentioned about sort of the practitioning of this field in, and of course, I especially have a heart for newer designers. I feel like a beginner. I’ve been doing this for 25 years, you know, of course different forms of this. It’s evolved. It used to be web design when I started you know.

So, I still feel like a beginner and I guess that’s what makes me qualified to host this show because I especially have a heart for newer designers that are jumping in and trying to navigate this is a crazy. It just gets more crazy and more evolved, you know, it seems like every day, you know what frankly and right. And so, I want to jump back a few steps when you were talking about kind of, you know, there’s unfortunately sometimes UX gets a bad name and I know that, you know, that sometimes probably it could possibly be with newer designers that maybe, you know, we’re just, you know, follow their gut, made a decision. Maybe it wasn’t the best one, you know, I’m sure that can happen, you know, these are all assumptions of course,

But I think that maybe one of the biggest problems that occur and please feel free to correct me or add onto this is in design is that when we don’t research enough and we don’t kind of get to know the audience that it’s intended for it. How do we find people, like how do we find the people that we’re designing for to talk to and research with. Like what are your best tips for those things.

Becca Kennedy: That can be definitely a challenge. I mean and I do want to backtrack and say that I think anybody like trying to do UX, like I definitely commend that. I love like we need to be more user centered in general and if people don’t feel like you’re doing it exactly right, like there’s no exact right way of doing it. You just get out there and learn and keep going. Yeah, absolutely. Iterations, the key to everything, right? And it’s something I even struggle with in my day job, so I’m the UX designer for Agoralist, which is a really great company and a really great product. We create software for indoor farmers to help them track their crops and operations. which is a great space to work in by the way because a sustainability sustainable food production is really important right now at the rate we’re going, we need some real food solutions or we’re not going to be able to feed our population in a few years.

Jason Ogle: That’s a bit scary.

Becca Kennedy: It is a bit scary or it would be scary if it weren’t for the fact that there are people doing really cool things with indoor growing technology. So, you can create a lot of food pretty quickly year-round using indoor technology, but anyway, that means the users

Jason Ogle: I love you said that real quickly. I love this kind of because when I first saw indoor farming, I going to say, should I put air quotes? But I know that’s only a small portion in a certain way. That’s not. I don’t think that’s going to help our civilization survives as much as what you can obtain, you know focusing on food. So anyway, thanks for clarifying.

Becca Kennedy: Yeah, yeah. We do focus on food. We do have some of customers as well, elsewhere in the world.

Jason Ogle: No judgment!

Becca Kennedy: Absolutely! A lot of valid reasons for that but our focus is on growing greens mostly, healthy foods in places that are considered food deserts. Right? So, if you live in inside a city, you might not have access to fresh food. So anyway, so users, that’s completely fine. The users of our product are farmers, right? They’re growers. So that’s not an example of a product where I can just take it to craigslist or take it out to Starbucks and like get gorilla feedback on the fly, right? Like they have to actually be people who understand the industry and know what they’re talking about to give any feedback. That makes sense. So for that, I rely on our existing customers, which is not ideal from like a strict research perspective, but from a user feedback perspective, it absolutely is because; they’re the people who I want to talk to you. They’re the people who are already using the product and know what they need from it and might not be getting or know what they like and want to let us know.

So yeah, it can be really hard. If you’re working on something that’s a little more of a general product and I’ve gotten research participants and I say that, but sometimes it’s a lot less formal than that. It’s just more like conversations, which is also fine, from Twitter, from Facebook, from walking around the campus, people are there. I mean depending on your budget and how much time you have on what your research goals are, you can get a lot of feedback quickly, inexpensively, and it’s as valuable as you make it. So if you know what’s important to get feedback on and you kind of like focus on that and use that to your advantage. You can get pretty far on not a whole lot.

Jason Ogle: That’s fascinating! What about—because; you have to again know where these people are, right, I mean a lot of people are on Facebook because even though they hate it, like the influencers even or on our Facebook because they go where the people are, right. That’s the whole thing. I just go where the people are. I’m kind of, I’m a contrarian. I guess like I just deleted my Facebook account. Like, I choose to not use that general because; I just don’t like Mark Zuckerberg very much, so that’s just me personally but, I think you have to know where the people are there. Do you have tips for kind of discovering that? I mean, I’m sure like if you dig into the marketing team, like what’s the email list even like for our customers that we can hit up for surveys or they have to come in and yes stuff like, do you have some input on that, like on finding where your people are?

Becca Kennedy: Asked around, you know, and depending on what it is, like I found people through like sometimes there’s Reddit groups that are specific to like what you’re researching. I mean every product is so different it’s a little bit hard, but just ask around also like who do you know, who’s interested in this or who do you know who kind of fits this bill? And like I said, if you’re doing in person feedback, you can even use craigslist, you know, and I think the key, no matter how you’re doing it, is to have a good screener in place. And by that I mean kind of just a few questions survey upfront to make sure whoever you’re contacting actually fits, who you want to talk to you. Yeah!

So, that’s what I’ll do is if someone contacts me and they’re interested in doing whatever the research is, I just send them a screener and ask them to fill that out and make sure they’re a good fit because you want to know who you want to talk to, but you also want to know like who you don’t want to talk to you. Like maybe you don’t want to talk to people who already use your product or you don’t want to talk to whatever the population is and you can weed them out that way and still like appreciate, you know, let them know, hey, I appreciate it. I’ll let you know if any other opportunities come up and then there you go, you’ve got an email address, but yeah, thought that is a smart tip for me.

Jason Ogle: Yeah, it is. I agree with you. And I especially love the screening because I mean, I think Josh Clarke told a story and his episode, Episode 9, where because I tend to ask my guests, do you have an awkward user testing story. And do you have one Becca?

Becca Kennedy: Oh Lord, I do.

Jason Ogle: Oh, good. Well, I’m going to ask his was interesting, like I’m pretty sure it was his where a homeless person came in to try to do the test and you know, it was no judgment or anything, it was just kind of like, Oh wow, I guess we need to kind of screen our applicants a little better, you know, but, you know, it was neat. I mean he took the test and he got the Amazon card or whatever it was at the sandwich or whatever it was, you know and such so but yeah, I think that’s really great advice though, because; you want to make sure that you try to get the right people in for that testing. And here’s another thing too that might be a good tip, and I’d love you to chime in on this to Becca, what your thoughts are on. I think Jacob Nielsen put it out there originally about the law of diminishing returns when it comes to the amount of participants in your test. And I think he says typically a six or seven is enough over you know, if you’re doing like, I think probably more qualitative stuff. I think if it’s quantitative you might of course increase that, but qualitatively I think you start to just get, like kind of diminishing returns with like 30 or 40 or 50 is like, okay, yeah, we could have probably gotten this trend after testing the first seven people, right. Do you have any thoughts on that?

Becca Kennedy: Oh yeah, definitely. I find that all the time and I, like I come from academia where it was all about like getting your effect size for statistics and you didn’t need to like a lot of people to run your stats and do your tests. But for me, yeah, usually after about three or four participants, you start hearing the same things over and over, so you have a pretty good idea of what’s going to be high impact changes you need to make. And yeah, you don’t really want to waste a whole lot of time and money on this stuff, you know, it’s better to do rather than say testing 15 people at once. I would rather do 5, you know, make some iterations; five again, make some more changes and then five again. So that’s what I will tell my clients when they come to that stuff because they don’t want to pay more than they asked to either.

Jason Ogle: Right, yeah! It’s like the law of asked you either diminishing returns on data but also on resources with the company. That’s a good point for sure. Do you have any stories of anything crazy or super awkward that happened during user testing speaking of?

Becca Kennedy: Yeah, I do. I told this story at the USPA international conference. There is typically a session called UX after dark, where everyone tells their most salacious stories and mine is not like, Oh God, yeah dude, there’s like some crazy stories involving nudity and just like creative. Mine’s not that. Don’t get too excited. But I had a real a hot mic issue, I’ll call it when I was doing usability testing for a pretty big project that had a lot of stakeholders and initially they had wanted, you know, like 6 or 8 people in the room with me while I was doing it. And I said politely, I don’t think that’s a good idea, that’s a little intimidating to have, you know, all these, like white guys in suits behind people as they’re trying to interact with this thing.

So instead I said, all right, but all setup, I think it was go to meeting or something like that. I said, I will screen share, you know, like I will record what’s happening and you can just log in and watch, right, without being able to interrupt or whatever. So I had my sound off and I will blame whatever the software was, I think it was go to meeting, but whoever it was, like, I purposely went in and made it so that any guests who joined the call would be muted, like I knew that was something that shouldn’t be there. For whatever reason, it doesn’t stick and I didn’t hear it because my sound was off, so thankfully participants heard nothing.

But when I went back later to listen to the sessions, you know, and like take my notes and follow up on stuff, there was a man who had dialed in and was listening in and was not happy. I’ll say that man, this thing was like his baby, right? And this usability testing was very new for them. So they threw it in very late in the process. They were ready to ship this thing and I was finding all kinds of bad stuff. So, as participants are going through and missing things, he’s yelling at the screen like, hey, it’s right there. It’s right. Come on, it’s right there. Don’t you see it? Scroll down, scroll down like that, like nonstop and I had to listen to the whole thing because I had to listen to my own interview and I had to just pause it every, you know, minute and a half or so and just walk away and be like, all right, this is fine.

At least I know what he really thinks. And even some his comments were kind of toward me like, come on, you got to help them out. Like that kind of stuff. And I’m like, dude, this is going really well and you don’t know it. So that’s my only – It was very awkward, very awkward because I also share the recordings with another team and I was like, listen, I’m really sorry about this. I thought I took measures to make sure this didn’t happen, but it did. There’s another voice on there. Just know that. Just know that. So yeah, that’s my story. It was a little bit painful. So check, double check that you’re not recording people who do not know they’re being recorded.

Jason Ogle: Oh, that’s really funny. I wrote an article that kind of touches on something similar, it’s called user researchers enjoy the silence. And basically, it has to do with just the whole premise of the horror movies, where you’re watching the horror movie and you always like the protagonist, like always seems to be like the third act where what he left relied really, it’s just this one person and they run into the dumbest right. Like they could get in the car, they could start the car that they came in. That worked perfectly fine when they got there and drive away, but they don’t. They run into the Barn, the barn. Right.

Becca Kennedy: And you want to yell at the screen…

Jason Ogle: You want to know what the screens and many people do, like what are you doing? Come on. But it just. I wrote about and touched on how we need to just be silent and some of the best data will reveal itself if we just embrace the awkward silences. So, we tend to want to cut it, just cover it up and just insert ourselves and you know, and we know all the answers. So that doesn’t help with data, kind of ruins the test, you know, that story.

Becca Kennedy: So important! You want to give people the space to feel comfortable with you. You don’t want to make them feel rushed. You don’t want to make them feel like they’re ever doing their own thing. So, that’s why I try to fight to not stakeholders in the room, when you overall works pretty well because, you know, I understand. I totally understand. But they have a tendency to want to jump in and help. It doesn’t help anything. And then I think it might start to make participants nervous too, like doing their own thing.

Jason Ogle: Exactly! And you mentioned the white dudes with suits on and I couldn’t help but think of like the matrix, you know, like you can just see Mr. Smith standing there with his little ear monitor, you know, like that is intimidating stuff. Mr. Anderson, we missed you. Great movie.

Becca Kennedy: The first one. Yeah I agree with that.

Jason Ogle: Oh that’s really good stuff. Oh Geez. There’s so many places we can go. I want to ask you, because I know you have many design superpowers, but I want to ask you, what would your design superpower be?

Becca Kennedy: I had a feeling this question was going to come and yeah, I don’t know. I think if I could narrowed down, I would say making things happen. So I mean, I talked to you a little bit about like making research happen on a budget and without the resources that you might want from a usability lab or like a giant company or behind you or whatever. But usually I can get things done and kind of scrappy ways, but it kind of works out and that’s why living in Albany kind of works for me because it’s a smaller city for sure, and maybe not most interesting or happening place to be. But I like being here because I can make things happen. Like I have connections, I’m involved in whatever things I want to be involved in and I feel like I can really, you know, make a difference in small ways. And that’s a really cool feeling. And I would call it a superpower.

Jason Ogle: Definitely. Yeah, definitely GTD, get things done, or some people would say GSD

Becca Kennedy: Not on this show. We don’t say that.

Jason Ogle: That right. And if you did, I would do a kapow.

Becca Kennedy: I know. I’m trying not to make you do that.

Jason Ogle: So, let’s talk about your design Kryptonite. Like what, you know, you obviously get crap done, but what kind of keeps you, what holds you back in this field? What’s your design Kryptonite?

Becca Kennedy: Oh, there’s a few things. Few things I could talk about, I would say. And it probably falls a little bit under imposters syndrome, like a lot of things to do, but when I get pressed too hard on things, sometimes, I get a little bit defensive and more like shoot from the Hippie, like to be honest. Yeah, because; UX is hard and that there is still some subjectivity involved. there’s still some kind of calls you make and you don’t know if it’s the right thing. You have data to support you hopefully. And you know, some intuition, but that’s not enough whereas, you know, when I was in more of an academic setting and in my research was scientific, it was more about like, well I can confidently say based on my results, based on my statistics out such and such and such and such, which in a way was more of a safety net, whereas an in-design setting, it’s a little more difficult, right?

So, when people actually pushed back at me, sometimes I don’t always handle that the best, not that I get crazy or anything, but I’m just like, I’m either, I say, all right. Yeah, maybe you’re right. I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know, I don’t know anything I guess or I’m like, well, I know what I’m talking about and you don’t.

So, something I’m actively working on is just like and my boss at my job, the CTO of the company, he’s like, yeah, it’s awesome. That’s fine. Just, you know, you don’t have to like respond to people right away. Like, because we’re a remote team, so we communicate in slack. We don’t, I mean, we have calls every day and stuff, but a lot of stuff happens in chat form and I’ll want to like respond right away and he’s like, you can just say, hey, I’m thinking about it and then come back to it in like 10 minutes, you know, and that’s something that I’m learning, you know, as like I’m getting better at the career on building. I’m like, well, all right, this is important to be able to not get defensive, you know, and just realize that, well maybe I didn’t quite communicate something as well as I could have or maybe you know, what, people don’t always read the things you put out, you know, they’re not going to read even if it’s like a one page brief, people want always read it. So it’s not personal.

I think sometimes it’s easy to take things personally in this field compared to some other ones just because; we have to fight so much for so many things. And I think it’s something where a lot of people think they can maybe quote unquote do UX. It seems like something that, you know, isn’t hard, I guess some people, so it’s easy for people to criticize some of my work as opposed to like, like a software developers work where if you’re not a developer that seems crazy hard, like I’m not going to question that.

Jason Ogle: Thanks for your vulnerability in that. I feel like that is an issue that every creative person struggles with, every single one. And I’m so glad to see the conversation coming into the fore front a lot more. In fact, by the time this airs, I will have already released a two part episode with Denise Jacobs who wrote a book called “Vanish Your Inner Critic.” Isn’t she wonderful?

Becca Kennedy: I love her. I can’t wait.

Jason Ogle: Oh, it was so good. I, and she is brilliant. She’s just so passionate to like about this subject and wanting to help people through it. And, it’s so clear. Comes through so loud and clear in the interview. And so, Defenders listening, if you hadn’t seen that in the feed, go back and check it out. And by the time again, this airs, that’ll be available. And so, Becca, when it comes to imposter syndrome, have you found any sort of, I guess, things that you can do or thoughts or if you found any sort of little ways to kind of overcome that? I know that you can never, I don’t think we can ever fully conquer it. That’s the thing. But have you found ways to kind of help silence that voice, that unwelcome voice?

Becca Kennedy: Yeah, I think just trying to separate what’s legit criticism or feedback from like coworkers for example, or clients or whoever it is from what is maybe them just not knowing what they’re talking about, but that’s an important skill worry is to understand like you can pull pieces of information from feedback that is useful even if it sounds like it’s not, even if it sounds like they’ve completely misunderstood something or whatever you, there’s always something that you can improve. And I think actively working on improving the things that maybe you feel you’re not great at or you know you’re not great at, kind of helps, because not everyone is going to be perfect at everything and that doesn’t mean you’re an imposter or just means you’re being honest with yourself.

Jason Ogle: Yeah. Well, that’s great advice and I think that it’s also knowing that you are an expert at what you’re doing, right? You’re right. It’s knowing that and being able and being confident enough in your skills to know that the person that is giving you that feedback, just give them the benefit of the doubt that they just don’t really know exactly what they’re saying sometimes. And here’s another piece of feedback that I got from Denise in that talk. And I love this. She says “you are not your work”. I like that.

Becca Kennedy: Yeah, that’s a big one because; I think it’s easy for us to get our self-esteem kind of tied up in what we’re producing because we feel so strongly and passionately about what we’re doing, but that’s not who we are. Yeah, of course. But that’s also not who you are. So if there’s a setback in your career or you get a rejection from something that’s not you, that’s just whatever you produced and you’ve produced a lot of other things that are amazing. So yeah, just keep some perspective.

Jason Ogle: That’s really great. I’m big on. I’m huge on personal growth and when I’m in my morning routine, it’s been so fluctuating since my accident. I had an ankle surgery in that. It’s been so fluctuating. I haven’t been able to really do it as much, but when I’m doing it, one of the first things I do is I do a journal and some would call it the five minute journal, where I list three things I’m thankful for and I list three things that I’m hoping to accomplish today. And then I do like an affirmation. I do like, you know, like kind of a self-affirmation on there. And it may seem cheesy and it may be hard to do, especially if you’re kind of uncomfortable like talking about yourself.

But you know, this is for you and I just recommend like I think that so many of us, especially some of them are the biggest imposter syndrome sufferers. I think they just kind of forget about all the winds. I think they forget about all the cool stuff they’ve done and contributed. And I think that this could be a way to kind of lock that stuff. And when you’re feeling discouraged and even if it’s not in a journal, like put it in an ever note doc, but all of it in one page, that might even be better because then you can, when you’re feeling discouraged, when you’re feeling like shut down or whatever, and like you’re no good. Go and read those things. You know like put a date on it, like this day is when I did this that day is when I did that, and look at the and here’s the result of what happened with that. I think that would be really good Defenders to do that, and just keep a wind journal, right?

Becca Kennedy: Oh yeah. Some people also will like when they get compliments will write those down or like if you get a nice email from someone, save that. Thank you from someone, just going to remember that like maybe on the hard days you forget that people do really appreciate what you do and value you and all of that. Yeah.

Jason Ogle: I know you surrounded yourself with people that have helped you get where you are, but I know you’ve also achieved a lot on your own. So I want to ask you, what would your UX Superhero name be?

Becca Kennedy: I think I would be something like the synthesizer, although I think having doctor and my name would be cool, but that doesn’t doctor synthesizers like too much of a mouthful. So yeah, the synthesizer I think because I am really good at taking information from different spots and synthesizing it together. So part of that definitely is from learning those skills as a PhD student and it’s just something I kind of am naturally good at it, I think because my interests are also super varied. So instead of being like really good at one specific thing, I kind of just know somewhat about a ton of things so I can pull in from information together whether that’s research information or whether those just like different ideas, combining them together and I think that would be me as a super hero or UX Superhero.

Jason Ogle: I love that. I love the synthesizer. That sounds awesome too.

Becca Kennedy: its sounds really cool. Yeah!

Jason Ogle: It has a great meaning.

Becca Kennedy: It’s like creating something from other things, right?

Jason Ogle: Yeah! I love it. And you know what, I noticed that about you too because when I was researching you and looking at some of the talks you’ve done and I could see that you have, you’re really good at pulling kind of a through line into your talks and in your presentations. I saw one that I was actually kind of surprised to see because; I haven’t seen a lot of your articles where you touched on this, but it’s kind of the robotic thing and the AI, I’m getting a little bit concerned about where we’re heading with AI and I’m starting to agree with Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking and you know, and which you really pulled into this presentation. There are some of their quotes that “this may not be a good thing when machines can self-replicate, intelligent machines can self-replicate and actually make their own decisions.” This could be a problem.

And then what I learned, I think my biggest takeaway that I had never heard before until I read that was about Isaac Asimov’s a who is an author of old me, his three laws of robotics. I never heard that. That was incredible. And by the way, I’ll link to that, Defenders I’ll link to the three laws, but it basically, it says, “robots cannot harm humans”. He basically says that in three different ways, three laws in three different ways, which is really incredible. And I think that that is more relevant now than it ever was before when he even wrote that, almost pathetic.

Becca Kennedy: Absolutely! Oh yeah. I gave that talk a few years ago. I’ve like stopped. It’s become overwhelming like trying to come up with that like everything happening with that, but in general, yeah. I’m also worried once we have artificial intelligence that is so intelligent that it’s self-aware and actually we have that. But like emotionally self-aware and everything, like we really need to start considering the rights of robots because at what point are they different from humans, at that point if they’re actually feeling emotion, if for example so do we, and I mean, what’s the difference, then one was created evolutionarily and the other created also evolutionarily, but just really, really fast.

Jason Ogle: That terrifies me. And I think that the difference, I guess the other big difference to me is that the robot was manufactured and so, everything that a robot may quote unquote feel has been, pardon the expression, but synthesize, right? It’s been completely manufactured. And what concerns me the most is that I don’t care how much on the outside a robot can like move their eyebrows and stuff like that it’s never going to have genuine empathy for humans, ever. And that concerns me because it’s, you know, over time, I think we may start to be convinced that they are, but it’s not true. So yeah, So, I’ll like to say like, I can tell that you were able to synthesize information quite well and kind of extract some really interesting stuff into what you’re sharing. So keep doing that. I think that’s awesome.

Becca Kennedy: Thank you so much. That’s nice of you to say.

Jason Ogle: Absolutely. And this is a fun one too, and I kind of want to caveat this question and maybe even start with another question. This is about users. And I read one of your articles just this morning actually about, should we call them users still, it’s inappropriate, you know, and you have a video in there and that I hadn’t seen before from Donald Norman and this is going back to 2008, I believe is what it was, and he’s at some sort of conference and he’s like saying, “I think we need to stop calling them users, you know, like, that makes us feel, that makes us out to be overlords and, you know, and it separates the humanity from who we’re designing for.” And I kind of disagree with that. I mean, I know Donald, he’s one. I mean, it’s certainly, I respect the guy at tons because he really is, was one of the, I think probably the father of a UX as we know it today.

But I would say that I know that he’s also kind of a sensationalist and I think he likes to kind of be a contrarian to which I can appreciate also, but I just feel like, you know, when you’re having conversations, and I’d love your perspective on this Becca, but when you’re having conversations as in a design team it’s just easier to say users and that doesn’t mean we have to feel a above them. I think if somebody who feels a designer is feeling like an overlord over a user because they use the word user, I think that, I don’t think the problem is that they’re using the word user. I think the problem is that with them that they need to kind of, you know, maybe take a step back in and just kind of do some self-evaluation and gain some humility. That’s my opinion about it. But I just think it’s easier in conversations to refer to them as users. Tron can’t be wrong.

Becca Kennedy: Yeah! Tron can be wrong. And that’s how I kind of ended my article like, I think it’s fine, but it’s good to like reconsider, you know, and you might be talking to people who are not using your product and then they’re not technically users, but I mean words are hard, so whatever. It’s fine. Just don’t forget that there are people, like they don’t just exist in the context of your product. That’s what I would say about that is just know that your product is just one teeny tiny part of their lives and it has to fit in with that or they won’t use it.

Jason Ogle: I like that a lot and I am going to wrangle and some psychology here and I think that we as designers, let’s make an association in our brain if we haven’t already, God help us. You know that users equal human, right? That’s my little rant about that. But I know that the tandem to this part is one of my favorite lines from Tron was when he said, “I fight for the users.” How do you fight for your users, Becca?

Becca Kennedy: Well, first of all, I love Tron. When Tron legacy came out, there was a time in Grad school or everyone who’s listening to the soundtrack, like nonstop in our labs because it was so good for like getting in the zone.

Jason Ogle: It’s Daft Punk, right?

Becca Kennedy: Daft Punk, exactly.

Jason Ogle: They did such a good job on that.

Becca Kennedy: I know I love Daft Punk. I mean old Daft Punk. Anyway

Jason Ogle: Jeremy Keith hates him.

Becca Kennedy: Who Does?

Jason Ogle: Jeremy Keith. Oh, well that’s an inside joke with Brad Frost, because Jeremy Keys, like a folky guy. He puts a little callback, as a call back to his interview. I highly recommend checking that out of the Defenders.

Becca Kennedy: I would say I fight for Users. You know what? I think I do that mostly through education, hating other people to be honest. I mean, of course in my everyday job and my consulting. Yeah, that’s what I’m doing. But bigger picture, I try to educate designers and developers and entrepreneurs about usability and user research and how to do that and how you can get feedback on things and why you should. And I think that has bigger impact than just my own personal work can ever really do because I hope that the message kind of spreads out and helps people design better and improve their processes. So, hopefully that’s working. That’s my goal.

Jason Ogle: And like you said, an example.

Becca Kennedy: Of what?

Jason Ogle: Teacher, Educator?

Becca Kennedy: Oh yeah, yeah, exactly. And I like to write article, like you said that usually are geared a little bit more toward like beginner designers or I should say beginner UX practitioners to help orient them to things they should know.

Jason Ogle: Absolutely! And Defenders checkout Becca’s writing, I’ll be sure to link to it in the show notes, but she really has a way of breaking down some very complex subject matter into really practical, understandable terms. I think that’s another one of your superpowers, Becca for sure. And I guess that is, you said you were synthesize things. I think that is an example of that, so we should have linked to that and check those articles out there really good.

Becca Kennedy: Oh, thanks.

Jason Ogle: So, let’s wrap up the show with the imparting of superpowers. What is one habit that you believe contributes to your success?

Becca Kennedy: I think supporting others actually contributes to my success a lot. So, people who I respect and admire, people doing good things, groups doing good things, initiatives just trying to help other people shine actually helps me out in the end a lot. Not like in a one for one like, you know, I’ll promote you, you, you promote me thing, but if you help other people do the things they’re good at eventually that might help you out in ways that you weren’t expecting, you know. And it helps me kind of gain an appreciation for some of the things other people are doing. Here’s an example, actually I have been supporting a local nonprofit for a while called Albany Can Code, and their mission is to create a job pipeline for software developers in the capital region of New York where we have not a lot of them really, and there are people who are fully capable of becoming a developer but just don’t know how.

So, it’s instead of, you know, getting a degree in computer science or whatever, it’s these practical shorter courses that help you learn what you need to know to get a developer job was starting to develop her job and I love them and support them forever, I’ve spoken on panels for them and I’m actually now taking one of their courses as a student to learn some front end development stuff so I can, you know, maybe not become a developer myself, but understand HTML and CSS and that kind of thing a little better, so I can collaborate better with other people. But that wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t been aware of the good things they were doing in the community and trying to just help them out however I could.

Jason Ogle: That’s so cool. I love that. And there’s a couple of thoughts that I had in this. There’s the rule of reciprocity, of course, that, you know, when you do something for somebody else, they naturally want to do something for you. But I love that. That’s not, that wasn’t, it’s not at all your motivation. You just really genuinely like to help other people. But something crazy happens when you help other people, they want to help you. It’s amazing, right? I mean, you know, sometimes that unless they’re jerks, right? But I love what the Great Zig Ziglar said. He said, “You can have anything in life you want, if you’ll just help others get what they want.” I really liked that.

Becca Kennedy: I love that.

Jason Ogle: Oh, so what’s your most invincible UX resource or tool you can recommend to our Listeners?

Becca Kennedy: Well, there are a few things I recommend to people and they contact me and maybe they might be interested in first getting involved in UX, one of those is there’s a slack channel for mixed methods. I don’t know if you’re familiar with that podcast, but there’s a lot of researchers and UX people in that slack channel and they’re very, very supportive and there are a lot of postings for internships and stuff and it’s really cool stuff that you don’t really find other places. And like a lot of slack channels, it’s also a place where people share articles or reading or whatever, ask questions, ask for help on different things and, and it’s a nice group of people and that’s a very welcoming space. So, I do recommend that as a resource.

I also sometimes recommend people check out the Interaction Design Foundation courses, so it does cost a little bit of money to become a member of the Interaction Design Foundation. But once you are, you have access to online courses that are related to user experience research and design and some cool topics, you know, getting into like virtual reality and some more niche things. But I find that those courses are very well designed, and of course there are courses available on a ton of other platforms to look at, but I do in particular like the Interaction Design Foundation ones because they do talk more about the research side of things and how to do more research. So yeah, those are my suggestions for resources.

Jason Ogle: I love reading so much. I love books. I’m very big fan of the written word. I have a feeling you are too, especially with all the reading you had to do for, I don’t know how many years in school, but I’m sure a lot. So, I want to ask you if you could recommend one book to our Listeners, what would it be and why?

Becca Kennedy: Well, Don Norman has already come up in conversation then. That’s the name a lot of people are familiar with. but if you haven’t read it, everyone I do suggest reading the design of everyday things, which there are a lot of books out there that are more like methodology specific, which can be helpful. But design of everyday things really gives you like the overall theoretical framework. I think like in a fun way, like he gives a lot of examples of badly designed things to understand what UX is even about and even when it was written it was called the psychology of everyday things, tying more into like human factors then what we would call UX now and then the name of the book changed to “Match The World.” So, I always recommend that to people if they haven’t read it. Some of the examples are quite outdated, which is also funny. So, give that a read if you haven’t.

Jason Ogle: Cool! Great suggestion. I’ll be honest, I haven’t read it yet and that’s, I need to now, especially since you’re not the first person that has recommended that the first super guest that has recommended that book to me. So, I’m going to read it myself. And by the way, Defenders, I have a partnership with audible. I think that book is on audible. I don’t know if it’s Becca, is that one that you would, you can get by just listening to versus is there a picture you can see?

Becca Kennedy: I would actually read it. Yeah, because; there’s a lot of pictures in there of like old things.

Jason Ogle: Okay! So, don’t get that book, but still sign up for audible through my affiliate link and I get 15 bucks and you get a free audio book you get to keep. So if you do that you can get a different book. There’s a ton of other books in there that are really good, especially around psychology too. I’m going to put out “Mindset”. I love that book. It’s by Dr. Carol Dweck about our potential that we can learn anything that we truly desire to that. You can do that by going to use the defenders.com/freebook. Thanks for checking that out. There’s my little plug. Last question Becca, what is your best advice and you’ve given a lot already which I greatly appreciate it and other Defenders do too, but what’s your best advice for aspiring UX superheroes?

Becca Kennedy: I’m not the first to say this, I’m sure, but just start doing it. you know, don’t wait for someone else to give you permission to just start redesigning things for fun, you know, like if there’s a website you hate, how could you design a better, whatever it is, some kind of service. If you want to add a little research like a survey and then redesigned something based on survey results or anything like that, that’s a good way of getting started if you can’t quite figure out how to get your foot in the door, it just gives you practice thinking through problems like that. And it also gives you something to point to kind of as a portfolio piece of like something you’ve done, even if it’s not something that actually goes into production and you never know what could happen, maybe those people could see it and like it.

And the other thing I would say my advice is to learn a little bit about the history of user experienced. A lot of people, when they come to me for advice, there’s nothing wrong with this at all, but they come to it from a graphic design background, which is, I mean, that’s absolutely great, I love. I have so many graphic designer friends. I respect that a lot and wanting to incorporate more human focus design and graphic design is amazing, but just understands that there is more to it than just you know, wire frames and prototypes that it is a whole way of thinking in a whole system approach to things. And hopefully maybe you learned a little bit from me babbling about that, but definitely just read up, you know where the field came from know that it’s not a brand new thing and know that research is important to it as well.

Jason Ogle: I love it. Do you have a recommendation or is there a book that has somebody written a book that kind of touches on the history of UX and kind of how it’s evolved? If not, I’m giving somebody a really good idea.

Becca Kennedy: That is a great idea. Yeah. I don’t know of to one to be honest. I know there are blog posts.

Jason Ogle: Yeah, Dr. Google’s there for you.

Becca Kennedy: Yeah! People have definitely written articles and blog posts on that too. So, if you just search like history of UX, I’m sure you’ll find some stuff that will be helpful.

Jason Ogle: Thank you! Yeah, and I love what you said about just start and you know, Bruce Mallory said that, you know, begin anywhere as one of his rules that I had an old advertising a professional and he wrote a bunch of rules but one of them was begin anywhere and I think that just applies to so many things.

So, Defenders, if you haven’t just jumped out there and just started doing something and you’re feeling the imposter syndrome, you just listened to Becca’s advice and just start, just begin anywhere. And I love the idea too of like, if you don’t know where to start, find something that you use all the time, that you just hate the UX for and just take a stab at it, reinventing that. You know what I mean? This isn’t like an official, like you don’t have to say I’ve solved the problem, but you said, you know, here’s some thinking that I had around this and put it on medium. Like some of those articles I found that really brought out, gotten a lot of attraction, you know, it’s neat to see.

And you know, what that could be a portfolio piece, you know, it’s for a prospective employer to see how you’re thinking about solving problems. So, I think it’s great advice, you know, and if you do that, can you tackle Spotify first please? Thank you. It’s CC User Defenders. No, I love that advice and you know, “it’s easier to ask for forgiveness than to beg for permission.” That’s a quote by Laura Lee, I think. Right? Okay! Well, very cool. Becca, can you tell our audience the best way to connect and to keep up with you because I know they’re going to want to.

Becca Kennedy: Yep, find me on twitter. I’m there pretty often that at Becca, Becca_Kennedy, K-e-n-n-e-d-y.

Jason Ogle: Awesome! Is there anything else that you want to share before we go that maybe I didn’t ask you or just anything that’s on your mind or anything like that to leave us with?

Becca Kennedy: I don’t think so. We covered a lot. I hope it was helpful for people. It’s intimidating to be even considered analyst of people like Alan Cooper, but. Here I am.

Jason Ogle: Oh goodness. You are here for a reason for such a time as this and I so, I just speaking of that, I’m just so glad that you agreed to be on the show. It’s an honor for me, Becca, to have you here and you are contributing so much to our field. I just applaud you and in and I just asked you to please continue. Please continue doing what you’re doing. Educating, you know, they there’s a quote that says, “when you teach something, you get to learn it twice.” And so, I know they’re learning you are, you know, it’s like you’re just contributing so much. I thank you for that. And last but not least, I just want to say as always, fight on my friend!

Becca Kennedy: Thanks for having me!

Hide transcript

SUBSCRIBE TO AUTOMATICALLY RECEIVE NEW EPISODES

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | Amazon Music | RSS Feed

USE YOUR SUPERPOWER OF SUPPORT

Here’s your chance to use your superpower of support. Don’t rely on telepathy alone! If you’re enjoying the show, would you take two minutes and leave a rating and review on Apple Podcasts? I’d also be willing to remove my cloak of invisibility from your inbox if you’d subscribe to the newsletter for superguest announcements and more, occasionally.